The invitation was to make/curate an exhibition focused on painting, and drawing from two collections, the Fondazione per l’Arte Moderna in Turin, and the la Caxia in Barcelona. I took my own passions for how meaning evolves in art as a starting point. I am compelled by how form is inextricably tied to both subject and content; and I find enormous meaning in how our apprehension of surface yields information about reality while at the same time generating illusions that are resonant with our capacity for imagination. These interests guided my choices.

As I spent time with both collections, I became focused on those works in which rectilinear and circular forms played pivotal roles, and I started to think about the various ways in which these two basic shapes resonate with the body, how they function to corral content, and how they contribute to marking the edges of artworks.

Paintings need walls to hang on, and for the last hundred years or so, the ‘white cube’ has been an assumed context for them. The white walls, and clean geometry of the space being proposed as a neutral container, not unlike a blank piece of paper. The OGR building, itself a skeleton of an industrial building from a former time, is not neutral. Importantly, it also has no built-in lighting system; and paintings need light to be seen. So, I needed to take account of both walls and lighting.

It is always valuable to acknowledge context as the edges between artworks and their surroundings are permeable, with information flowing in all directions. In this case the buildout for the exhibition is not proposed as neutral. It is in concert with the history of the white cube, with the space and history of the OGR, with the artworks themselves, and also with the history of my own artwork.

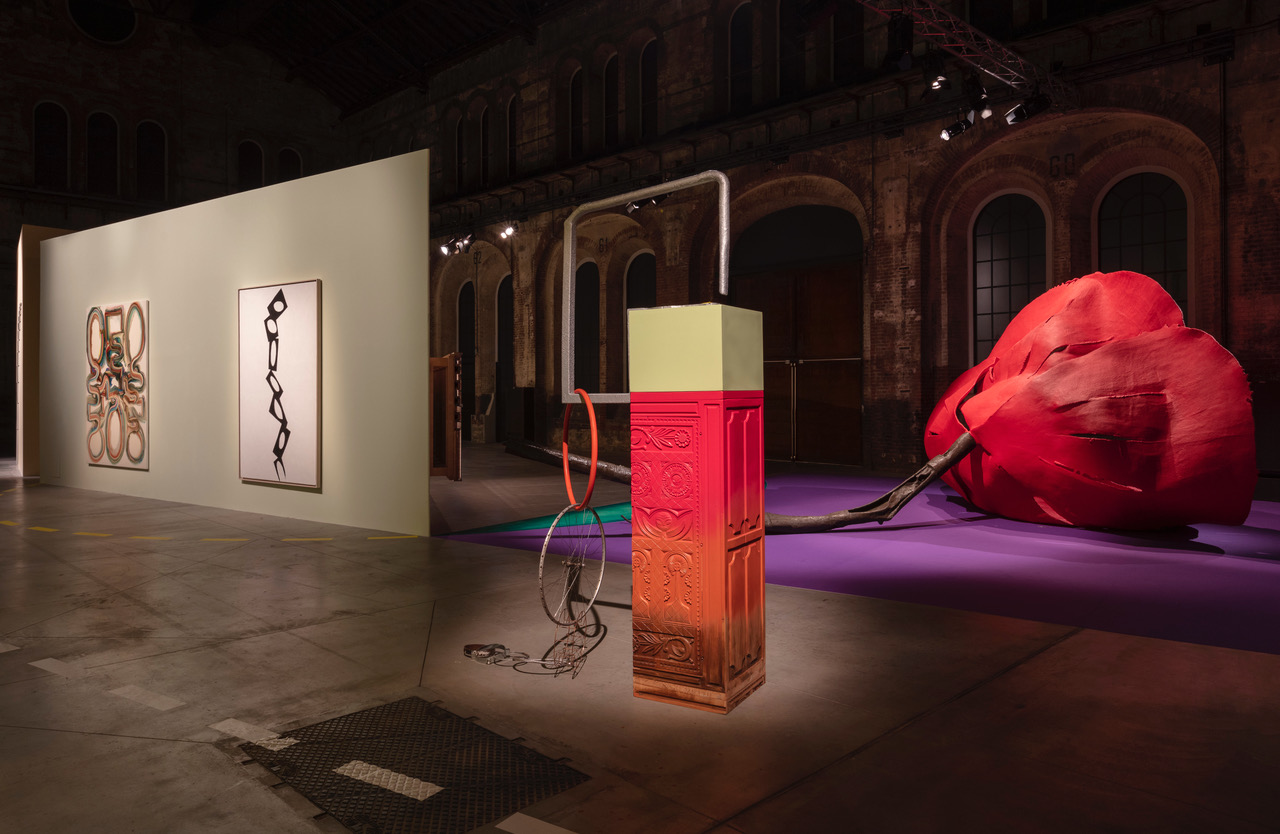

The first essential elements of the buildout are the triangular wall structures. Being that triangles are fragments of rectilinear forms; they are always full of dynamic energy. Their corners point out past themselves, carrying the eye and attention in three directions. I proposed two clusters of triangular wall structures each related to a shaped piece of color on the floor – one round and the other square. Each island, and each artwork, in the space is lit inside of the otherwise dark building, turning these clusters into Floating islands.

The bright, floating, painted islands of paintings seemed to require a foil of some kind; a need satisfied by the introduction of a facsimile of a wrestling rink. Like the many paintings in the exhibition, and like the walls they hang on, the rink relies on rectilinear form to orchestrate action. The rink’s floor offers an opportunity to hold vibrant color as paintings do. In this case a vibrant pink that drips over its edges. In the real dimensional space above the rink’s floor one can imagine entangled bodies engaging in intense action akin to the action playing out on the flat surfaces of the paintings hanging on the surrounding walls. Or one can move one’s own body into the rink. The floor functions as foreground and background at once. The imagined wrestling bodies are very present! They could be, like the floor, pink; or brown, beige, tan, or yellow. Yves Klein’s Anthropometries body prints come to mind here. The rink is bounded by a stretchy border. It is as full of theatrical promise and artifice as are the situations we fabricate to facilitate the presentation of paintings.

Like the other two floating islands, the rink is also spot lit, seeming to float in the otherwise dark space of OGR.

In addition to conventional paintings, the exhibition includes many works that make use of painterly tropes, and objects that may or may not be paintings, depending on how one defines the genre. As in so many instances in life, the categories we us to classify art objects are often useful abstractions applicable to particular instantiations, but insufficient to address the complexities of all. We engage parallel struggles regarding our use of category when we consider gender, age, race, aggression, wealth, strength, weakness, all of which, at various junctures, escape boundaries of thought when it comes to the particular. In this exhibition I am most interested in considering how painterly qualities and conventions move through the exhibition rather than fitting each work into a category.

While most paintings included in the Western cannon are rectangles, there are also tondos, or round paintings. Robert Mangold’s Curved Plane, 1995, proposes a half circle as the whole painting. Many, but not all, paintings are framed by the edges of a rectangle. And sometimes a painting asks that we put together a number of rectangles sequentially to create a whole. Clemente’s fresco of 1996, Pedro G. Romero’s Sodoma y Gomorra Año, from 1989, all work in that way.

A few photographs have slipped in, in deference to their reference to, and appreciation for, their recording of painterly moments. Amendola’s photographs of Alberto Burri cutting plastic with a torch in which Burri is drawing a circle in an off the shelf rectangular plane of plastic. This is at once painting and sculpture. Vito Acconci’s photo collage of himself preforming an action, or drawing with his body on a plane. Uliano Lucas’s photo of a Piazza that includes a painted drawing on the ground; in this case the geometry serves to organize public space, and the action within – here a kiss.

Paint itself is a kind of skin. Paint forms a skin on the walls that paintings are hung on as well as on the canvas of the painting. In this way the skins of paint in the exhibition function as both foreground and background.

Taking account of the cavernous brick space of OGR, and thinking about how to create a situation that both speaks to the complexity of what painting is while at the same time allowing the works themselves to be fully empowered, I remembered the staging of space in Lars von Trier’s film Dogville. In this film a drawing on the floor maps out rooms, making space for our imaginations to fill in the room’s physicality as the action in the film plays out over the floor drawing. Here, as in Dogville, I treated the floor as an evocative plane out of which the action sprouts.

It is difficult to say whether this exhibition design grew in response to the space of OGR, or if the nature of the two collections gave rise to this treatment. In any case, at first blush, looking through the two collections, I was struck by the many works in which the circle and the square intersect. Often, but not always, these works present literal circles and squares. I began to think of the representation of the human body as a kind of circle inside of the square; and Leonardo DaVinci’s Vitruvian Man came to mind. Many of the works in this exhibition present circles, triangles, and rectangles as overt imagery. I came to see the imaged human body as a rough kind of circle framed by the rectilinear painting. Klein’s Portrait Relief of Claude Pascal is a good example. Of course, the blue body in this work can also be seen to be resonant with a rectangular shape; the body can be seen, and understood, with the aid of many different kinds of geometry. Unfortunately, this work was not available to include; I mention it in any case as thinking about it gave rise to the pink wrestling rink.

The life of the investigative imagination is instrumental in forming us and the world we share.

I hope that this exhibition provides an opportunity for those who pass through to take pleasure in flights of fancy, and to value their own agency as they take in the extraordinary range of world building encompassed by this collection of works.

Miguel Ángel Campano Tara, 1994. A picture of a stacked rectangles with round holes in them. This picture is itself a sort of black hole in the rectangle that is the painting.

Francesco Clemente Miele, Argento, Sangue, 1986. The fresco is divided into four rectangular planes. There is a face of sorts on one, that turns, at least for a moment, all of the planes into geometric bodies. Bodies acting like architecture, with the lines between all working hard to create order amidst the pictorial undulation of the surface.

Marlene Dumas The Prophet, 2004. The man in the rectangle bracketed by the circle of his cape stretched out to hold him.

Bernard Frize Taunus, 1997. Paint acts here as an index of the circular motion of the hand and arm. The action of the body within the frame of the painting can be seen as analogous to the moving body inside of the wrestling rink. In both cases the roundness of the body is foregrounded in opposition to the rectilinear nature of the plane on which the action takes place.

Robert Mangold Curved Plane / Figure XI, 1995. A half-circle capturing four stripes and three ovals. The ovals are contained by the edges of the half-circle while the stripes can be seen to go on forever.

Guilermo Perez Villalta Flagelación, 1993. The painting makes use of a severe geometry as it depicts two figures, one controlling and violating the other. Either harm being done, or consensual erotic play. In either case, the very formal geometry inherent in the painting resonates with the behavior of one figure controlling the other. As the formal geometry ‘controls’ the representation of controlling behavior within the image, so too the rectilinear edges of the painting control the illusionistic properties of the painting. The images of human beings are confined, held, and organized by the geometrical representation of the floor and architecture. The bodies in this case are resonant with rectangles. The three sticks on the left side of the painting form an X of sorts, and seem to mirror the two human beings plus stick on the right side of the image.

Pedro G. Romero Sodoma y Gomorra, 1989. The mushroom cloud is a round, the door panel is rectilinear, and the man in the middle is both. Things are a little out of whack, we know, as the height of the door panel doesn’t match. The math isn’t adding up both in relation to form and to the impact of the nuclear bomb.

Edward Ruscha 9 to 5, 1991. A painting of the work day. A cycle of time contained in the rectangle that is the painting. A segment of time which we have conceptualized as circular with the analog clock, and in relation to the rotation of the planet, and also as linear in its unstoppable continuity. This work cuts out a segment of time from the flow; there is a kind of violence in that that mirrors the violence inherent in our conception of the workday. The enforced sameness of many workdays exists as a kind of circle inside the linearity of time.

Richard Tuttle Crickets, 1991. The painted, softened, rectilinear bodies of the sculptural forms harken to each other across space. To ‘cut a rug’ is to dance well and energetically. This work does just that.

Vito Acconci Directions, 1969. The photograph, documenting a performance, images a man arms and legs spread evoking Vitruvian Man. The man is framed by the stage, establishing scale and edge; in that way both the performer and the photographer are availing themselves of a painterly trope. The stage becomes a picture plane against which the man’s movements are drawings.

Aurelio Amendola Alberto Burri, Morra, Combustion, 1977. Cutting a circle in a square. The forms are simple. The torch and the melting plastic are virulent. The material in the end holds the memory of the body in motion and the intent that drove it.

Monica Bonvicini Bonded ed eternmale, 2002. Two chair bodies wear the studded black leather that human bodies might be adorned with, performing on a red-carpet surface – not a pedestal.

Jan Dibbets Comet Land/Sky/Land 6° -72°, 1973. The circle is carved out of the stacked rectangles. When one stands in front of this work the top of the arch is above one’s head. The human body standing in front of the empty wall space the work describes causes the curve to turn into an arch by virtue of scale comparison.

Simon Dybbroe Møller Waiting for Different Times, 2008. Carved wooden blocks, squeezed into a box of sorts, together present a sort of picture plane to us as we stand in front of it. But each block is dimensional, and it is as if they are all stuffed into a closet. The whole work exists not just on the wall, but inside of it.

Tracey Emin Dolly, 2002. The human orifice in the center of the square painting is round. It is small on the body, but looms large in consciousness. The target of many taboos, and discomforts. The source of unease and pleasure. The site of many nerves.

Hollis Frampton (Nostalgia), 1971-1972. One after another, rectangular photographs are placed on top of, and cover, a round stove burner. As they burn, they shrink, becoming small squares inside of the circle, and then morphing into charred organic shapes until they disappear. The voice overlay describes the images, once or twice matching the imaged photo. About memory in its many forms.

Mona Hatoum Undercurrent (Red), 2008. The floor surface acting as picture plane presents the square inside the circle, surrounded by light. A kind of celebration of elemental forms.

Jim Lambie Metal box, 2012. The piece is not made of stretched canvas but the layers of folded aluminum each present a painted surface that is bounded rectilinearly. The corners folded in point to the middle. The very idea of middle is evocative of roundness, even before the folded corners round off the square. An effort to see more at once than the surface allows.

Uliano Lucas Piazza Caricamento, Genova, luglio 2000, 2000. The embrace on the edge of the painted circle. Engaging the circle of life.

Reinhard Mucha Seelow (Für François Robelin), 2003-2006. The not words of all the materials organized by the oval on the billboard sized rectangle.

Claes Oldenburg and Coosje Van Bruggen Dropped Flower, 2006. The sepals, petals, stamen, and pistils of the poppy flower coalesce, drawing attention in the same way as does the asshole of Tracey Emin’s Dolly. The flower is couched in the rectangular purple carpet it sits on.

Diego Perrone Untitled, 2011. This human face, skull and ear, captured by red pen, is both circle and square.

Lawrence Weiner A REMOVAL OF THE CORNER OF A RUG IN USE, 1969. Words, given form on the surface of the wall. They, like paint on canvas, and make use of the picture plane the wall offers. Words both point to, and are the result of, the power to generate metaphor that is embedded in our experience of material. These particular words pointing to a ‘corner’ and a ‘rug,’ to absence and presence, raise a question about use value, and to the process of making, that resonates with the space between the making of the exhibition and the art objects contained.

Rachel Harrison Kouros Descends Stairs, 2008. In this work the kouros (archaic Greek statue representing the ideal beauty of a naked youth) has been reduced to a rounded lump set upon a rectangular stair. The stair also acts as pedestal for a collection of rounded fruits: apples and pears. There is a rectangular plywood board slapped onto the side. The action in this work is contained, and bounded by these two forms. Gender plays an understated role here in that the title refers to Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase in which the nude is female.

Jessica Stockholder Squeezed orange actor stack: Ode to Liz Larner, 2020. Produced by OGR to accompany this exhibition Cut a rug a round square. The work explores different kinds of attachment as curves move into angles and found objects blend into abstract shapes.